Article contributed by Dr. D. Kall Loper, Vice President of Digital Forensics and Incident Response at Cyderes

The Cyber Threat landscape is constantly evolving. New threat groups merge and rebranded threat groups monetize their attacks on businesses. Cyber security incidents are clearly on the minds of corporate directors thanks to the National Association of Corporate Director’s (NACD) tireless efforts to elevate this issue to the specific attention of accredited board members. The U.S. Federal Government has also elevated the issue through numerous initiatives under the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA).

Managing the impact of cybersecurity incidents is becoming part of corporate governance and leading practices across all industries. How can executives educate themselves about this rapidly evolving threat in a way that enables meaningful action without becoming security professionals?

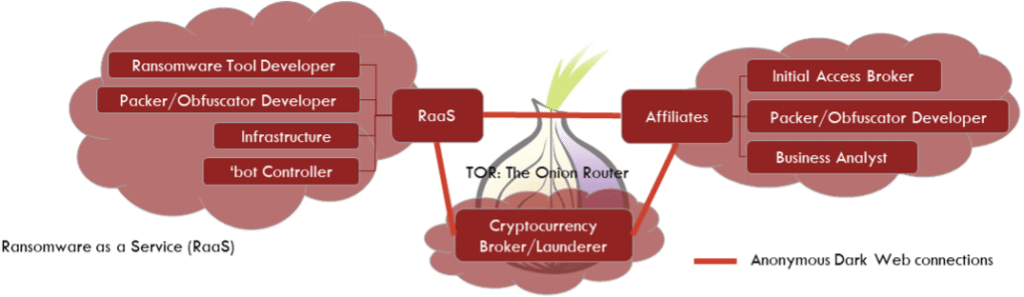

In the diagram below, three groups compose the major functions in a Ransomware as a Service attacker. Each function may be one person or many. Each person may be anonymous to all others or known only to a small collective. These functions may also be hosted as enterprises out in the open in friendly nation states. They may even be adjuncts to nation state militaries and intelligence agencies.

This diagram presents observable and testable inferences derived from the effects of attacks over the last few years as ransomware attackers have evolved. Generally, the RaaS actor (left of diagram) provides technical tools, techniques, and procedures through documents to affiliates. The services, tools, and document vary between attackers, but the general model holds true. They may also include infrastructure for name and shame (exposure of stolen data for the purpose of extortion), but again, there are variations.

The currency broker (center of diagram) specializes in paying out the funds in spendable currency and making cryptocurrency transactions harder to trace. Government and financial service industry interventions have made these necessary in many cases.

Finally, the affiliates (right of diagram) and their subcontractors select targets, gain access, and implement the attacks. Affiliates range in autonomy and may even develop their own branding in the underground economy.

The table below presents an analysis of the diagram and draws intelligence from the underlying facts. Further discussion of these conclusions is found below the table.

| Analysis | Description | Actionable Intelligence |

| Relationship among anonymous partners | Economic relationships are enabled and controlled by the Dark Web (often TOR networks) and cryptocurrency. Affiliates choose targets and attack, RaaS provides tools and infrastructure, Brokers launder and anonymize payments. | Relationships without trust must adhere to rigid standards of behavior. Attacks take on a predictable course. |

| Affiliates use RaaS services to attack |

Reputation and ability to monetize attract affiliates. Breakdown of an affiliate relationship yielded a Raas group’s playbook suggesting vulnerabilities to exploit, password templates, and server IP’s. | There are competing interests among the players. |

| Economics and resources dictate attack patterns | Infrastructure needed for dump sites has increased and become more vulnerable; stolen data volume has been impacted. RaaS providers hosting data limit the amount of stolen data posted. | Attackers predictably target less data, but with greater value for extortion and resale. |

Relationships without trust must adhere to rigid standards of behavior. Attacks take on a predictable course.

There is a truism that attackers constantly innovate; this is misleading. They do innovate, but not in all ways at all times. Attackers become complacent and rise or fall in standing as they innovate to overcome problems posed by security teams, IT teams, and law enforcement. The old self-propagating ransomware rarely works on even moderately prepared victims. Security and the enterprise targets have evolved defenses. Some innovations are so successful that they bind the attacker to a competitive advancement—like RaaS.

Simply viewing the attacker as a rival enterprise, rather than an omniscient boogeyman, allows us to take advantage of their evolutionary dead ends. The RaaS attacker has formed an alliance that allows rapid technical advancement but is now dependent on that predictable method. As defenders, we can shift our efforts to anticipate predictable actions. We can emphasize response and recovery instead of hoping for better technical tools to prevent the attack. We should be just as ready to shift our efforts if the RaaS attackers start to die out and new innovations rearrange the threat landscape.

There are competing interests among the players.

The ransomware threat group, Conti, developed a sophisticated corporate structure and franchise-like affiliate instruction books. When Conti leadership made statements about the war in Ukraine, they forgot or ignored the fact that an affiliate was based in the Ukraine. This affiliate released a trove of Conti documents that damaged Conti. While more dramatic, this is not the only example of competing interests among attackers. There is competition among threat actors to recruit affiliates. There is an unregulated system of economic relationships with no recourse to courts that should yield significant advantages to defenders, forcing the actors to innovate with greater risk and chance of failure.

Threat groups have also fragmented and reformed numerous times in the relatively short life of RaaS. In spite of their reputation for innovation, there are a limited number of paths to attack data that can be readily monetized. Attackers now focus on seeking targets of opportunity to access attractive targets. For years, discussions with CISOs have indicated that they don’t want to outrun the bear, they just want to outrun the other victims. This strategy may be playing out. Attackers’ “innovation” is to go after everyone, and brands are being built in the dark corners of the Internet for groups to specialize in an industry or particular victim set well-served by their particular methods.

As differentiated groups become more specialized, they also bind themselves to economic mechanisms with untrustworthy – often anonymous – partners. This presents opportunities for law enforcement and government intervention to disrupt and exploit relationships among the attackers. Incident responders can also benefit from understanding this relationship. Root cause for a ransomware incident may be located months in the past as an unrelated Initial Access Broker (IAB) achieved access and waited for the right buyer. These are effectively two separate attacks bound together by a completely separate transaction leaving no evidence in the targeted systems. Breaking any part of the chain of events (even those outside a technical attack chain) can benefit the victim enterprise.

Attackers predictably target less data, but with greater value for extortion and resale.

The goal of the attacker is to monetize their effort as quickly as possible and with the least risk. Attackers formerly cast malware into the ether or broadly scanned for open ports and vulnerabilities. As defenses adapted to this tactic, attackers shifted their focus on active intrusion and borrowed stealth from live-of-the-land attacks using minimal malware to affect the attack. Attackers quickly pivoted to stealing data for extortion as well as encrypting data for ransom. New innovations include data auctions and holding back the most valuable data from name and shame sites.

In a pure act of economic rationality, attackers have enhanced the stealth of their attacks by seeking less data, but also placed less investment in infrastructure in their name and shame sites. The innovation allowing this tactic relies on one of several techniques that can be used to anticipate and understand the part of the attack that is not on the victim’s systems. First, a stable and experienced affiliate base could identify valuable data to scare victims into paying extortion. As an alternative, the attacker must rely on the services of a business analyst by forming a business relationship without enforceable trust. Finally, the attacker may create an elaborate playbook for affiliates subjecting their methods to exposure and making them predictable.

Conclusion

Cyderes threat intelligence teams combine efforts to bring the most timely indicators of compromise and attack to customers. Cyderes offensive security teams harvest tools, techniques, and procedures to properly emulate attackers when testing customer’s security. Cyderes Digital Forensics and Incident Response teams test these conclusions through observation and investigation of incidents impacting customers.

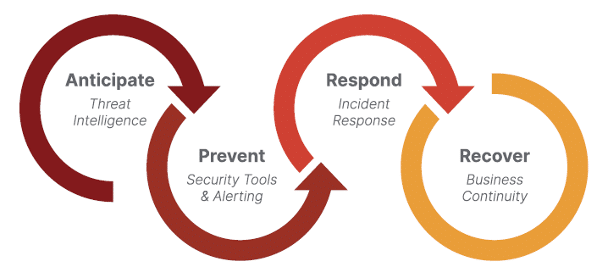

Cyderes DFIR also hosts the Threat Analysis Center (TAC) which is dedicated to developing business insight and actionable solutions that go beyond the technology. The TAC explicitly builds on the expanded security model presented in this work: Anticipate, Prevent, Respond, and Recover to build the full security motion to counter the attacker. The key to success in these efforts is to present the business understanding of the cyber event, informed by the technology but not exclusively dedicated to it. TAC findings are often configured into executive briefings, targeting upper level executives and Boards of Directors.

At Cyderes, we are dedicated to equipping organizations like yours with the necessary tools and expertise to combat the ever-evolving threat landscape. Schedule a time to connect with our Incident Response team today.

For more cybersecurity tips, follow Cyderes on LinkedIn and Twitter.